Madhupur rainforest, in north-west Bangladesh, is a place overflowing with natural beauty. Between the towering sal trees, wild green waves of edible and medicinal plants flourish. In the uppermost branches, monkeys play and the songs of brightly coloured birds fill the air.

To the indigenous Garo people who live here, this forest is more than a home. In the Garo language the name for it is A’bima – ‘Mother Earth’. Like a mother, the rainforest has provided them with everything they need. They in turn have taken care to preserve and nurture the forest, in all its natural splendour – they take only what they need to survive, respecting the delicate balance of the local ecosystem.

But it is, in part, because of the natural beauty of the rainforest that the people of Madhupur now find their home, and their very existence, at risk. Plans for an Eco Park – a nature resort for wealthy tourists to visit – threaten to force the Garo people from their land. Land they have lived on for centuries. The land of their ancestors.

Fearless and determined Garo women and men are standing up to this injustice and saying no – this is our home – you cannot force us out or pretend we do not exist. We are here. We’ve always been here. We’re staying.

And by supporting Hands On, you will join the Garo community in their fight. This page will be continuously updated with stories of bravery, images and videos that show the beauty of nature (and why it’s at risk), recordings of traditional poems and songs, and testimony to the power of marginalised communities standing in solidarity for the good of all.

Thank you for joining the journey.

A walk in the rainforest

January 2024

In this first update we take a walk with Polanto, a Garo village leader, as he shows us around his rainforest home and warns of the threats his community face.

“I enjoy living in the forest because my forefathers lived here,” Polanto says, as he strides confidently through the tangled undergrowth. “When I hear the birds singing, I feel fresh, fresh in my mind and in my heart.”

Polanto is the village leader – or Songnokma in the Garo language - of one of the many indigenous villages of Madhupur. He is relatively young to hold a position of such responsibility, but no less determined to do whatever he must to ensure the future of his community.

“I am a guardian of the community,” he says. “They honoured me with that. When any family or person is in trouble, then, as a chief, I go to them first to help. Of course, it is a stressful job, but it is my duty to serve the people.”

Polanto walks on through the jungle behind his home. He stops frequently to point out wild plants and mushrooms – here is one that can be used as medicine, another that is a favourite flavour in curries, yet more that are extremely nutritious or rich in vitamins. Each time, after describing the uses of each leaf, bud or berry, he sighs. All these valuable plants are becoming scarcer and scarcer.

Soon, it is easy to see why. The native sal trees - all different heights, branches bending off in all directions sheltering a huge variety of smaller plants - suddenly disappear. In their place, row upon row of straight, grey, branchless trunks, every one near identical in height. Eucalyptus – a cash crop planted in swathes on land that was once home to thriving natural rainforest.

“This type of tree destroys the environment and destroys the fertility of soil because eucalyptus trees consume huge amounts of water from the soil,” Polanto explains. “Because this type of tree grows fast, they get a lot of money in a short time – that’s why people want to plant these trees. When this type of plant is grown, they auction the trees and sell them, then cut them. There is a natural jungle here and they cut this jungle, these trees, and then plant the eucalyptus trees. Of course, this type of activity destroys the animals, birds and other creatures.”

He passes the eucalyptus plantation and another grove of native foliage, and finally reaches his destination. A clearing in the forest lets sunlight shine down on a river of vivid green shoots. This is the community’s rice paddy, where they have traditionally planted their staple food crop together.

If the Eco Park project is completed as planned, this area will be flooded to create a lake for tourists to swim in and relax by. The community have already faced threats while planting their crops.

But Polanto and his community have no plans to back down.

“I use this slogan: ‘Our land, our mother.’ My land is my mother, I won’t let it go. Our mothers, our forefathers, our fathers have died here, so this land is ours.”

How your support is helping Polanto’s community

“I’d like to say thanks to the staff of Caritas and other organisations. They sacrifice their lives to serve the community people. In bad situations and good situations, always Caritas is with us.”

The people of Madhupur are not alone. Your Hands On donations will help support local experts from Caritas Bangladesh and the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA) as they work closely with the community.

One of those experts is Brilliant Chiran – a member of the Garo community who works for Caritas.

Finding strength

The sunny courtyard of Polanto’s family home buzzes with activity as he returns, his children racing out to greet him. He smiles warmly as his son tells him about the time he saw a wildcat, and how scary its roar was.

Sitting on his porch in the afternoon sun with his wife, Liya, Polanto seems calm, and less serious than before. He no longer has to be the brave, authoritative leader, but simply a loving father and husband – if only for a moment.

“If you want a happy family, you must divide responsibility,” he says, “work, farming, domestic work. I have a good relationship with my wife. We are best friends. I feel very lucky to have such a strong bond.

“When I feel stress, I get help from my wife. She says: ‘I am with you. Don’t be worried.’ This is my coping mechanism. I get strength from my wife.”

Liya laughs when he says this, and replies: “He encourages me too. When my husband wants to do something, I tell him, no problem, I am with you, you can do it. I’m always with you. He is always supporting me too.”

The sun sets over Liya and Polanto’s home – but not on their fight for justice.

A threat at the rice field

May 2024

In this update, you will see more of the dangers the people of Madhupur face. Hear Kowshola, a farmer and a grandmother, tell us how she and her neighbours stood strong when they were threatened just for planting rice on their land.

Warning: The following video contains weapons and threats of violence. Some viewers may find this content disturbing.

How to prove your existence

You may be thinking: surely it must be illegal to claim someone else’s rice field and flood it – and to threaten them when they try to return.

In most cases, you’d be right. But what if the other person doesn’t exist? Or rather, what if they don’t have the correct paperwork to prove they exist?

The Garo people have lived in Madhupur for centuries, since long before legal documents were needed to prove their right to the land.

So, when powerful groups with interests in the land began to claim parts of the Madhupur rainforest, the community had no formal paperwork to prove the land was theirs. Even worse, there have been repeated attempts to deny that there are people even living here at all – to claim the Garo communities don’t exist.

“The project aims to support the Garo community in finding hope through asserting their rights to indigenous land, and enabling this through establishing legal and documented tenure of land. It is so important to the Garo people to have security and certainty. This will enable them to live full and flourishing lives and also to give future generations firm foundations to build their lives on.” Philip Talman, CAFOD’s Bangladesh Programme Officer

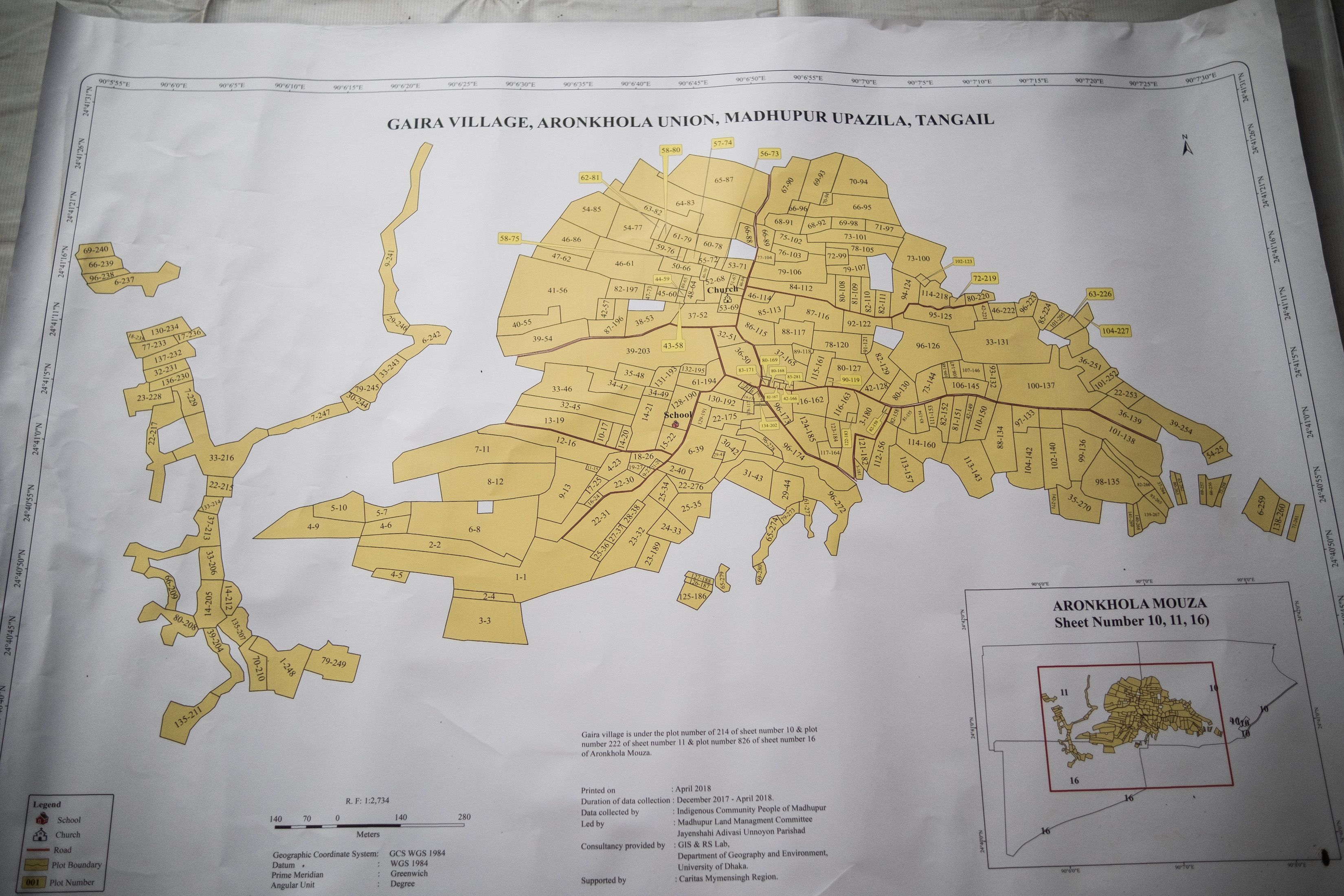

“Caritas gave us the chance to demarcate our land using digital land mapping technology. This was a good thing,” says Eugin Nokrek, president of Joyenshahi Adibashi Unnayan Parishad, an important council of the indigenous populations of Madhupur. “We measured the size of the land, the distance, the longitude and the latitude, and we have submitted these maps digitally and in hard copies. Our main demand is people should get their traditional land recognised legally.”

The cry of the sal forest

September 2024

In this update you can travel with Wilson as he rides his bicycle through the rainforest, singing traditional Garo songs and telling stories about the community rice field. But before we meet Wilson on his bicycle trip, you'll hear about the power of music from two young Garo musicians, Bimol and Liang.

The cry of the sal forest

September 2024

In this update you’ll discover the power of Garo music, hear from the young Garo musicians, Bimol and Liang, and follow Wilson, Kowshola’s husband, on his journey through the forest.

We’re a Garo band, we come from Garo land

Bimol and Liang are in a band called The Achik Blues. Bimol’s the frontman and lead guitarist. Liang translates the songs into the Garo language. Their music is often about the struggle for land rights for indigenous people in the Madhupur forest.

“Music is not just for entertainment, it’s a tool to raise our voices for change for our community.”

Bimol is cool, calm and confident. He leads the conversation with natural comfort and humour. He regularly bursts into loud, infectious laughter or belts out a verse from one of the band’s songs.

The Achik Blues perform regularly in Dhaka, the capital city, as well as locally. They’ve come back to Madhupur to seek approval from Garo elders to hold a music festival to raise awareness of land struggles. They want to call the festival: Cry of the Sal Forest.

“As Garo people, music is in our blood,” continues Bimol. “It’s our culture. We have our own instruments. We have our own types of lyrics. We express our culture through our performances. We describe our experiences through dance and through sound.

“We are trying to tell stories through our music. We perform in the Garo language, but wherever we perform we try to explain in Bengali or in English what the songs are about.

“Music has no language. It has an incredible power to bridge cultural boundaries.”

This is the music video for the first official song by the Achik Blues. It reflects the injustices faced by indigenous people in the Madhupur rainforest.

Photo: Liang Ritchell, Garo youth leader and Achik Blues lyricist, is a keen supporter of local artists and musicians

Under the rubber trees, no other trees will grow

Liang is a youth leader in the Garo community. He works voluntarily with young people, educating them on their rights and training them to raise their voices against injustice.

He is serious and stern and talks passionately about the history of Madhupur and his people's fight to maintain and protect their land. He grows visibly angry when recounting the injustices his community has faced:

“Whenever the forestry department bring a new project, they never want to sit with us and talk with us, they never want to adopt the ancient indigenous knowledge or culture. We have the experience of living in the sal forest. We know that under the sal trees, there are other plants that grow naturally and easily. But under the rubber trees, or eucalyptus, no other trees will grow."

“There were so many fruits in the trees to eat, we didn’t need to bring anything else. But now the young generation will never have that chance, as the forest has already been destroyed. Now we don’t have any fruits you can go and eat. In the past, we didn’t have to think about our lunch; I knew that when I went out into the forest, I would find enough food for the day.”

Maintaining the Garo legacy

“We have knowledge to survive here without damaging the forest,” continues Liang. “For example, when we harvest the wild potatoes, we never collect the stem. When other people come to this area they try to copy us, but they collect the plants as a whole which means they can only collect it once, because they destroy the plant. When we do it, the plant survives and can give us potatoes again next year. The wild potatoes are gradually becoming extinct.

“Our old generation never thought just of us – they also thought about nature and the whole forest. That is why we maintain their legacy – the culture of saving the forest.

“We never want to destroy the forest. The forest is our life. We live through this forest.”

Meet Wilson

Like Liang and Bimol, Wilson is also a Garo singer-songwriter.

Wilson is a respected elder in the Garo community, a rice farmer and proud grandad. Wilson knows that his land rights help to keep his family and community safe.

“The land is important because from this land I manage the food for my family. I feed my children and my grandchildren. When the forest department threatens to evict us, I feel bad."

“They are snatching the food from our stomachs.”

Wilson is also one of the people Liang describes who’s passionate about passing on that Garo legacy: the culture of saving the forest.

“My age is about to finish,” says Wilson, “but the children, our future generation, they must become educated, practice our culture and realise the importance of tradition – this is my hope.”

Cycling through the forest

Wilson’s good friend Monu lives a short cycle away through the forest paths. When the day’s work is finished, Wilson goes to see him. He cycles past the sal trees, past the modern farms, past the community rice paddy, wishing his neighbours well and singing Garo songs proudly.

Follow Wilson’s cycle through the forest in this exclusive interactive video. Use your computer’s mouse to move the camera around and immerse yourself in Madhupur.

Like mother, like daughter: protecting their forest together

In this update, you'll meet Mironi. She is a strong mother figure not only to her daughter, Mukta, but to her entire village. You'll learn about her inspiring leadership and how she unites the Garo women to protect their forest.

“Big mother”

Meet Mironi a leader in her community. She speaks confidently, standing with pride in her garden humming with wildlife. Her voice is controlled. She only pauses a few times to sing along with her daughter, Mukta.

As a mother, Mironi is the head of her family. But she also plays a vital role as the 'big mother' of her community.

“If there is any problem in a family you must go to the mother to solve it, so if there is a problem in the village they must go to their ‘big mother’.”

Mironi is the ‘big mother’ in Madhupur. This means Mironi is the person to visit if you have a dispute with a neighbour. She helps solve disagreements between community members with patience and kindness.

“People come to me, and I listen to each person’s point of view, and then I help them understand how we can live as a village – with unity.”

Mironi highlights the importance of solidarity. She knows that to protect their forest they must stand together as one.

A wall of women

“Hundreds of women came to stand side by side and say: ‘If you want to cut our banana trees, you have to cut us.’”

Mironi inspires the Garo women to fight injustice. Thanks to your regular gifts, CAFOD funds a local group that supports Mironi’s community. This directly helps Mironi educate the women in her community on how to protect their beautiful Madhupur forest.

She was the one to inspire the women to unite when the army arrived.

Mironi remembers the armed men forcing their way onto the Garo people’s land. They were heavily armed with machines to cut down the forest.

But Mironi led a peaceful protest.

Hundreds of women gathered. They linked arms. One strongly holding on to the next. Together they formed a human shield. Standing between the armed men and their precious trees.

“The armed forces were coming to cut the banana trees down. The women were the ones who went and stood in front of them – because we believed it is easy to arrest or torture the men, but not the women.”

That day the women’s bravery inspired the community. They knew together they could build a better world for the next generation.

“From then on, the women became fearless, and the men saw that we can help protect our land. So, it wasn’t just our words, but our actions, and our bravery that brought people together.”

Mukta walks in her mother’s footsteps

In Madhupur, women pass their leadership roles and property to their daughters. This means Mironi’s daughter, Mukta, will one day be the ‘big mother.’

To learn how to lead, Mukta joins Mironi on her community visits. Mukta listens to her mother’s lessons and feels inspired.

“When my mother is talking and trying to resolve any conflict, then the people listen and accept what she says easily. They trust my mother, so it is easy for her to resolve any conflict in this area.”

They have a strong mother and daughter relationship. This bond helps Mukta learn vital leadership skills for the future.

“We have a strong bond. We feel proud of our strong relationship. Our strength comes from each other.”

One day, Mukta will be the mother figure. She will take on Mironi’s incredible legacy as a woman everyone trusts.

But for now, Mukta and Mironi lead together. Mother and daughter inspiring women to create real change.

Next time…

This story will be regularly updated as your Hands On gifts help the community in their fight for their land. Join us again for the next update!