The longest journey

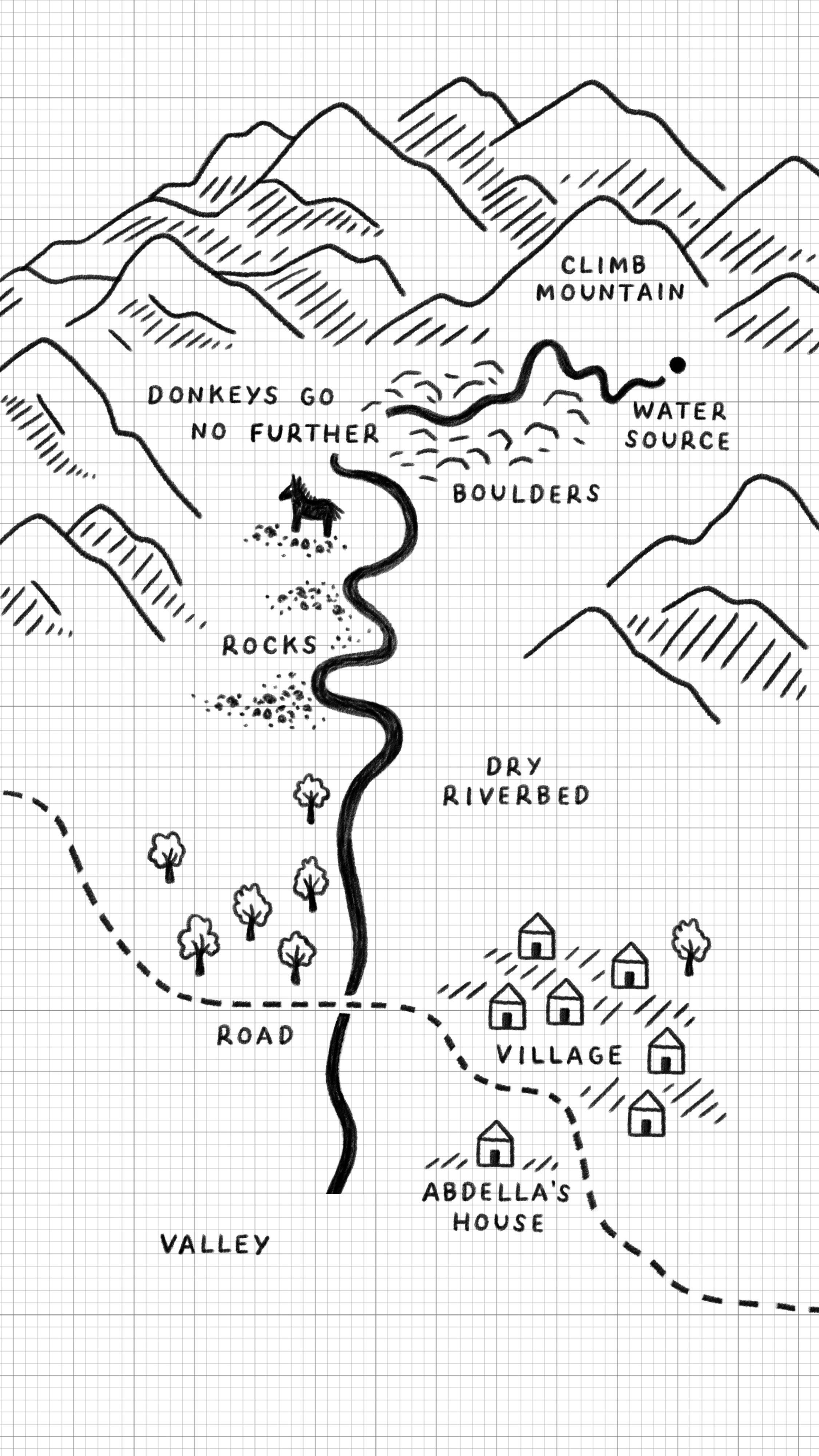

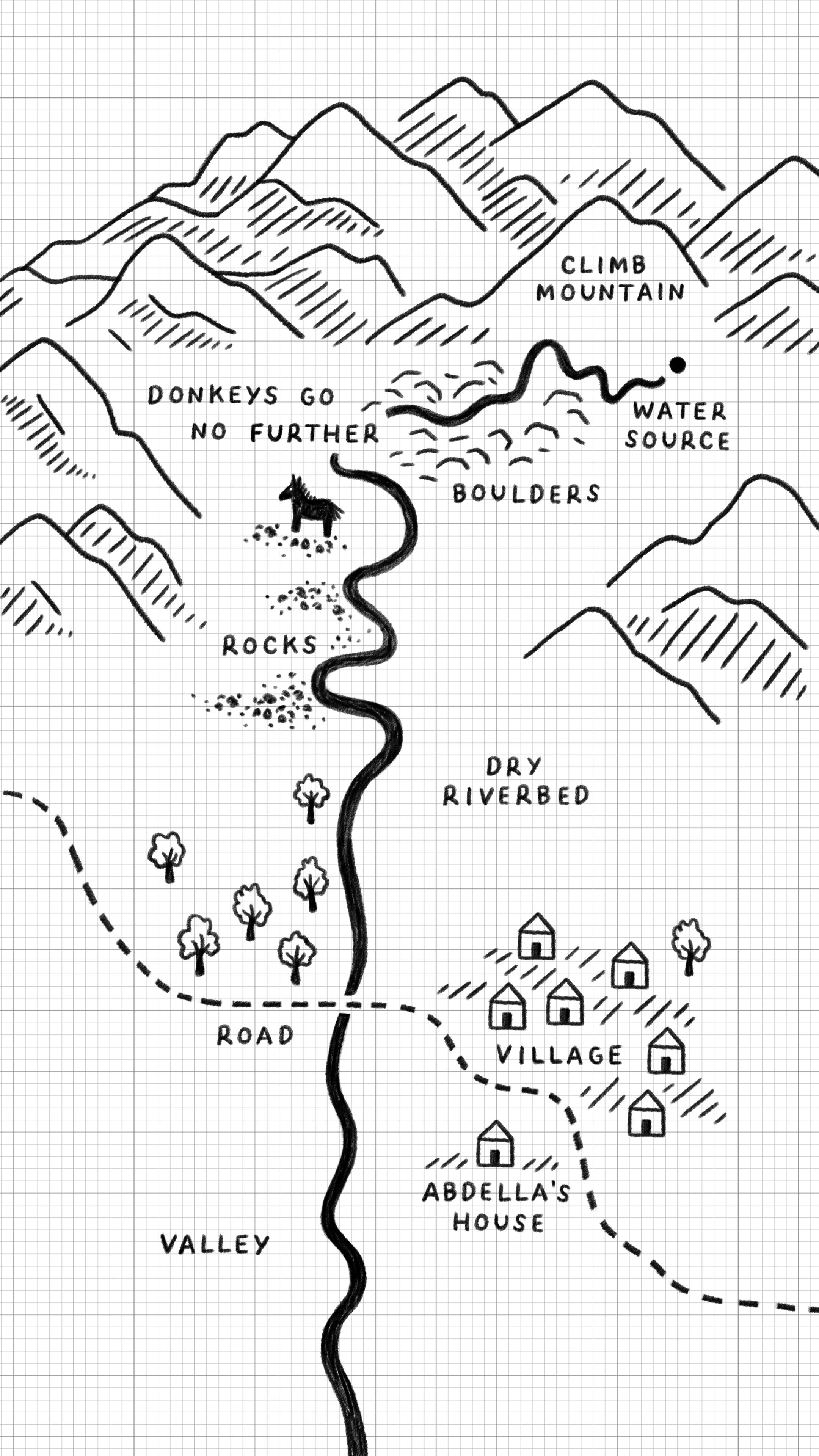

Abdella is about to start a journey that will take him ten hours. The journey is a matter of life and death. It is the long walk for water that keeps his family alive.

Blinking into the early darkness outside his home, he worries that he’s already behind time. He has to move soon.

Far off in the hills, hyenas yip. A camel groans into the gloom. There is an outline of a shrub - one of the few plants that can survive out here.

The donkeys kick and scuff, ready for the water containers he straps to them. Two containers apiece.

A glance to the north, far up into the path through the mountains. The side of the mountain is where Abdella will be in a few hours. Walking, scrambling, climbing. This is where he has to be before the sun gets too high and it’s too hot to travel.

One last look back to his home, the two small shapes side by side: his sleeping nephews, both too young to make this journey themselves. He leaves food in the pot for them. When they next see their uncle Abdella, he’ll sit smiling, handing them both a precious glass of water.

Abdella coughs. Without food or something to drink, the desert settles in your throat.

“We need to go now,” he says to me, glancing to the east where the sun will rise.

Then Abdella sets off along the dried-out riverbed near his home. This is a journey he has made ever since he was a boy - the long ten-hour walk for water to keep his family alive.

Home: The hottest place on earth

There is an Ethiopian saying: “One thinks of water only when the well is empty.”

The saying may come from an area where there isn’t any drought in Ethiopia. In the desert regions of Afar in northern Ethiopia, water is never far from anyone’s mind.

A devastatingly beautiful place. A devastatingly hot place. If you stop there, away from a town or village, you’ll first feel fear. Fear that you will quickly die from exposure and dehydration. Your mind will race: “What happens if I run out of water? How will I get out of here?”

It’s not cowardly to think like this. It’s practical. It’s human.

This vast place called ‘The Danakil Depression’ is frighteningly big, hot and dry. If you peer across the land after ten in the morning, you will see the heat shimmering over the incredible desert.

Abdella’s neighbours talk about how precious water is. “When I am collecting it, I think about it. When I’m not collecting it, I think about it,” one says. Water is essential here, the biggest issue.

Around the world, women and girls often bear the burden of carrying water. But in this part of Afar, everyone must walk for water.

Water shortage is a worldwide problem. The World Health Organisation states that one in three people around the world – over 2.2 billion people – don’t have access to safe drinking water. Of people who live in rural areas, one in eight people don’t have access to basic facilities like toilets, places to wash hands and drinking water.

It’s important to remember that since 2000, 1.8 billion people have gained access to water.

But for Abdella’s community and hundreds of millions around the world, climate change is making it more difficult just to stay alive. Rising temperatures, and less rain that falls in unpredictable seasons, will mean that water is more scarce with greater numbers of people looking for it.

£20 can buy water containers for two families

Abdella lives in Afar, Ethiopia - one of the hottest, driest and harshest places on earth. Temperatures here are regularly way over 40 degrees celsius. Life-threatening droughts are common, animals die and people suffer.

Access to safe drinking water is one of the biggest challenges the region faces, with 70 per cent of Afari children deprived of access to water. Drinking water shortages are common because there are few surface water sources like ponds or streams in Afar, with many people reliant on shallow, traditional wells that are unreliable and often dry up during frequent droughts. When these sources dry up, Afari women and girls are forced to walk long distances just to find water for their families. This can leave them vulnerable to violence.

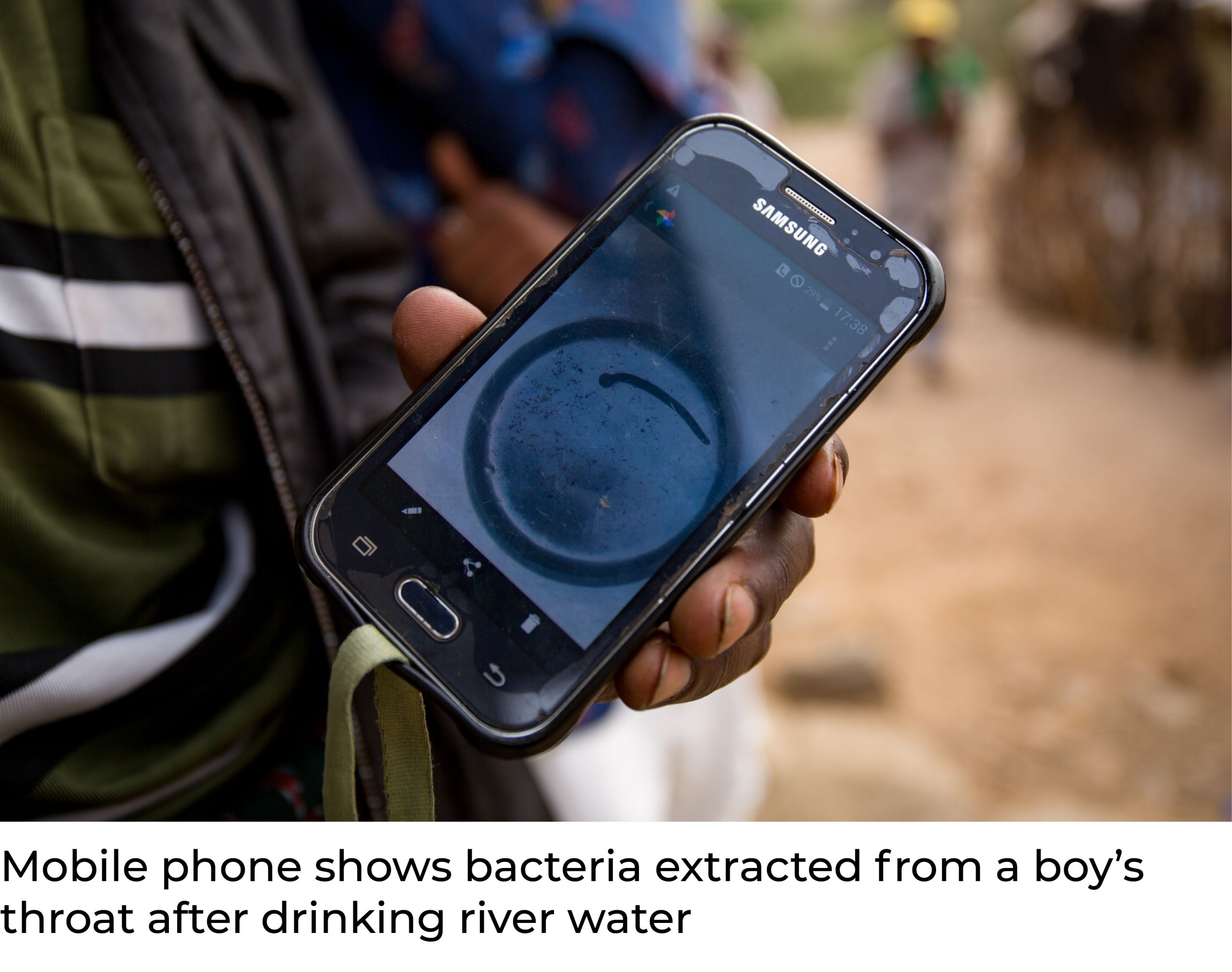

Water shortages and unsafe water sources have contributed to cholera outbreaks, increases in malnutrition as well as decreases in livestock productivity and other livelihoods.

The donkeys won’t go any further

An hour or so in, Abdella arrives at the boulders – a long range of large rocks, six foot high by six foot wide. This presents a new challenge.

“The donkeys won’t go any further,” he says. “They will stay here.” He loosens two jerrycans from one donkey and takes them in his hands.

He offers his hand and helps me up onto the first rock.

He has a simple, but gruelling system: take two cans to the water hole, fill one and bring it back, leave the other at the water point – he can’t carry two safely. He’ll then carry another two to the watering hole and bring one back. Then he’ll make individual journeys for the last two. In total, Abdella makes eight trips from donkeys to water point and back again.

The boulders rise slowly – one on top of the other. The sun is rising too. It’s now past eight in the morning. “Time is not a friend on this journey,” says a neighbour.

The donkeys won’t go any further

An hour or so in, Abdella arrives at the boulders – a long range of large rocks, six foot high by six foot wide. This presents a new challenge.

“The donkeys won’t go any further,” he says. “They will stay here.” He loosens two jerrycans from one donkey and takes them in his hands.

He offers his hand and helps me up onto the first rock.

He has a simple, but gruelling system: take two cans to the water hole, fill one and bring it back, leave the other at the water point – he can’t carry two safely. He’ll then carry another two to the watering hole and bring one back. Then he’ll make individual journeys for the last two. In total, Abdella makes eight trips from donkeys to water point and back again.

The boulders rise slowly – one on top of the other. The sun is rising too. It’s now past eight in the morning. “Time is not a friend on this journey,” says a neighbour.

A young girl is making the climb to his left. She lifts herself over the rocks with a container in her hand. Abdella shouts a greeting to her from the bottom of the rocks. She waves back.

That pause to look around the landscape when he first left his home may come to haunt him. Time is precious. He must keep going. The sun won’t relent out of pity.

Straight ahead now. Lifting the left leg. Push up. The journey doesn’t get easier. The smooth rocks will punish careless climbers. There are people who have hurt themselves badly here. Broken bones. Serious wounds. These rocks are no cushions.

He lifts himself further up as the climb begins. Up to a shrub and a glance back.

Abdella's friend is following. Mohammed is a similar age and has made the climb for the same amount of time as Abdella. He slows a little, but he can’t afford to wait. The sun doesn’t wait.

To his left, fifty feet away, some goats career down the hillside. Scattered rocks come tumbling after them. Luckily, the girl Abdella greeted just minutes ago has already moved on. She would have been pelted by the rocks otherwise.

Thirty minutes or so go by. The rock scramble comes to an end. Relief. Abdella's limbs must be aching; mine feel like they’re on fire.

Yet Abdella now stands at the hardest physical part of the journey: the climb. Here at the foot of the mountain, the most dangerous section of Abdella's walk for water begins.

The most dangerous part of the journey begins now

Three and a half hours in, this is the foot of the mountain. “This is the most dangerous part. We have to go on, we have to move now,” says Abdella.

He starts climbing. If he stops now, his tired muscles will struggle: thirsty for water; hungry for food.

Hands working, legs working. Hands reaching for rock, hands reaching for scrub to hold. A glance to the top of the mountain – all clear, no goats, nothing that will send rocks skittering down onto him.

Injuries happen here. Miles from a hospital and medical help, people get hurt. In this incredibly remote place, an ambulance can’t get to within two hours of a person. To get help, you'll need to be carried out on the back of a donkey.

The water containers clatter, old and yellow and battered from the journeys.

The most dangerous part of the journey begins now

Three and a half hours in, this is the foot of the mountain. “This is the most dangerous part. We have to go on, we have to move now,” says Abdella.

He starts climbing. If he stops now, his tired muscles will struggle: thirsty for water; hungry for food.

Hands working, legs working. Hands reaching for rock, hands reaching for scrub to hold. A glance to the top of the mountain – all clear, no goats, nothing that will send rocks skittering down onto him.

Injuries happen here. Miles from a hospital and medical help, people get hurt. In this incredibly remote place, an ambulance can’t get to within two hours of a person. To get help, you'll need to be carried out on the back of a donkey.

The water containers clatter, old and yellow and battered from the journeys.

The climb starts now. Four hours after setting out in the dark. Abdella has made this journey so many times, but he can still feel it. In his legs, his feet, his hands.

“I don’t think about anything when I climb,” his friend says later. “You can’t. You can’t let your mind wander. You think about where your hands and feet go. You think about getting through different parts. You think about the heat of the sun. You think about where you’re putting your hands – are there snakes there? You think about where you’re putting your feet so they don’t slip. You think about getting to the top.”

Breathing heavily now. The hot air winding around inside him. Another breath keeping himself full of air. A cough, particles from the desert jump into hungry lungs like this.

Higher. Lungs needing more air. Limbs needing more air.

And now the top. He climbs up onto the plateau. Just time to take in air now. To take some moments to get his breath.

From this point he can see the world. His home down there – the small main building and then smaller rooms. He can see the dried-out riverbed he walked through hours ago. He can see further out to the desert where no one lives. In the distance somewhere, he knows a community has a water pump. It’s a long way away, but he knows it’s out there.

A final look down into the valley where he’ll begin his descent. Somewhere down there, in this remote and ancient part of Ethiopia, is his prize: water.

The climb starts now. Four hours after setting out in the dark. Abdella has made this journey so many times, but he can still feel it. In his legs, his feet, his hands.

“I don’t think about anything when I climb,” his friend says later. “You can’t. You can’t let your mind wander. You think about where your hands and feet go. You think about getting through different parts. You think about the heat of the sun. You think about where you’re putting your hands – are there snakes there? You think about where you’re putting your feet so they don’t slip. You think about getting to the top.”

Breathing heavily now. The hot air winding around inside him. Another breath keeping himself full of air. A cough, particles from the desert jump into hungry lungs like this.

Higher. Lungs needing more air. Limbs needing more air.

And now the top. He climbs up onto the plateau. Just time to take in air now. To take some moments to get his breath.

From this point he can see the world. His home down there – the small main building and then smaller rooms. He can see the dried-out riverbed he walked through hours ago. He can see further out to the desert where no one lives. In the distance somewhere, he knows a community has a water pump. It’s a long way away, but he knows it’s out there.

A final look down into the valley where he’ll begin his descent. Somewhere down there, in this remote and ancient part of Ethiopia, is his prize: water.

The simple solution

“The water we get here is not good,” says Abdella about the water point he goes to. “The monkeys and hyenas use it, it makes us sick.”

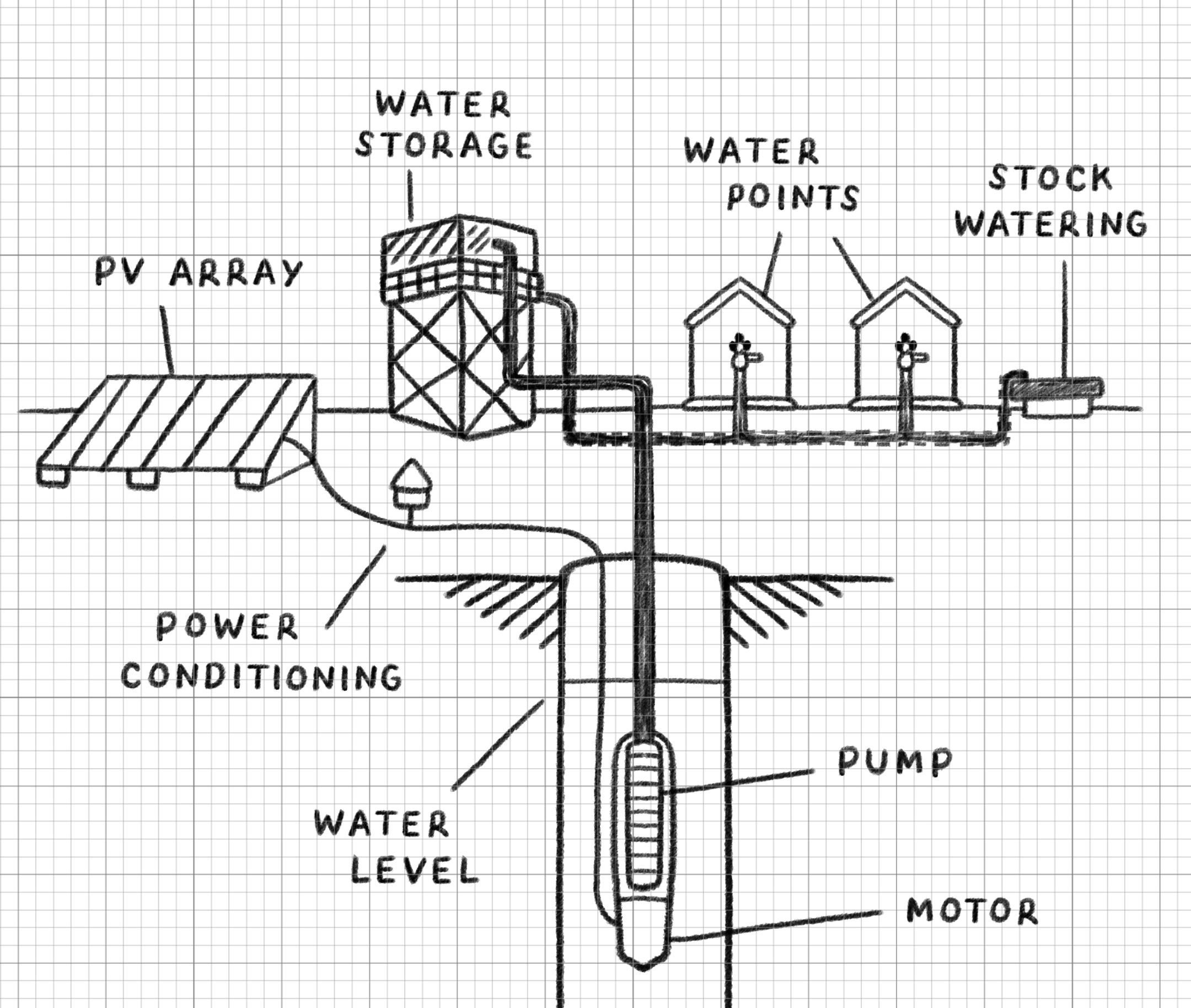

A solar-powered pump will bring water to hundreds of families living around this small and basic water point.

The sun will power a motor that will run a pump, which will pump water from groundwater reserves.

Because the pump is run by a solar-powered motor, it means that everyone can collect water in the same amount of time. The little girl Abdella saw on the rocks will spend the same amount of time collecting water as he will.

Please give today to help more people like Abdella around the world.

Donate today and you could bring water to someone’s home.

£20 can buy water containers for two families

The pump would also be closer to their homes – not ten hours away in the mountains.

The water point would also be a far less dangerous place with cleaner drinking water. Wild animals would frequently visit and drink from the old water point. Queues would also move quicker – this is one of the reasons it takes so long for people to get water.

The local professionals who can help

Abebe Belachew is CAFOD’s Climate Change and Adaptation Officer in Addis Ababa. He has years of experience and expertise in the field and works closely with the professionals who help communities like Abdella’s in Afar.

“We work alongside people who live locally – often coming from the communities they help. They are people who might have spent years in a professional field and so have outside experience – water engineers, agronomists, public health experts, teachers, for example. They might have studied in a field they’re helping.

“Here in Afar, CAFOD works alongside a group of aid professionals who are very close to the community. They stay in people’s homes and work with them to tackle the problems they face. They are known and trusted. This means they can get to communities other charities might struggle to reach or be allowed access to. It also means they understand the problems that the people face and don’t impose solutions on them.

“I’m really proud to say that the engineers we work alongside go above and beyond what is expected. Some travel long distances on bicycles to get to pumps and boreholes. The determination and passion everyone shows for these projects is an inspiration to me.”

Water no deeper than your fingers

Hours into the journey, time feels like it is speeding up, chasing us. I know I have been slowing him down today. We’re hours behind. This first journey would normally take five hours, he’d take the water back home and then go out again to get more. Today, he may have to go out again at night.

Now, the scramble down the mountain. At points, Abdella disappears.

After winding down the mountain and walking along worn desert ground, we see it: the prize. Abdella strides towards it - a pool of water no deeper than your fingers and not much larger than a dinner plate. This is the source of water that keeps Abdella's family alive.

He is exhausted and breathes deeply. There’s no one here. Sometimes there are others here and Abdella has to wait 30 minutes to an hour just to fill his containers. “When there is drought,” he says, “we wait days here. It’s difficult to sleep because it’s so uncomfortable. It’s dangerous.”

You must remember how important the community is to people. You can see this in the unwritten rules for water collection. No one takes more than they need; if they do, they deprive someone else. No one takes longer than they need to; if they do, others will suffer in the sun. People wait their turn. You don’t take someone else’s water.

Your transgression could be a matter of life and death.

Abdella pauses to take some air. The sweat beading on his forehead. Then the routine he’s known since he started – scooping water into his jerrycan.

“How do I feel?” he says, busying himself over the water containers. “I feel tired. The other people coming here are tired. You are tired. I have nothing more to say.

“I am a young man. I feel I am wasting my life. I want to start a business selling small goods like soap, oil and sugar.

“I want to make something of my life.”

Despite the difficulty, the exhaustion, the loss of time, every journey Abdella makes is a victory. He has fought to collect water for his family. He has kept them alive.

The long journey back.

Exhausted and bruised but most of all thirsty, he arrives in the tent where he started this morning. Beads of sweat on his forehead, gasping for breath.

Then there’s this feeling that beats everything else: lifting the flap of the tent, seeing his nephews reaching for him, beaming. The joy on their faces when they call for ‘Uncle Abdella’. And him pouring each of them a glass of water.

Nothing compares to that shared moment of love.

£40 can buy safe water for a school

What CAFOD does

Abebe and his colleagues in Ethiopia work closely with teams and organisations throughout Ethiopia to bring not just water to people, but to help them stand on their own two feet.

It’s through local experts such as those Abebe works with that we are able to help the most hard-to-reach people around the world.

We are part of the Caritas Church network – one of the largest aid networks in the world. This means we can reach out to people in 165 countries. And because we are part of the Church network, we can go into places other organisations are not able to, because they might be too dangerous, or the people don’t trust outsiders.

It is extremely important to us as a Catholic aid agency that we help everyone, regardless of faith. We live out our faith and see these life-saving and life-changing works as an expression of our faith.

Your support is crucial in allowing us to reach vulnerable people around the globe who continue to struggle with the things we take for granted.

£20 can buy water containers for two families

£40 can buy safe water for a school

Words: Mark Chamberlain

Design: Jessie Keable-Elliott

Photography: Louise Norton

Tech Lead: Philip Abbott

Built with Shorthand